MANTRAYA POLICY BRIEF#45: 31 DECEMBER 2022

Limits of Pakistan’s Afghanistan Policy

SHANTHIE MARIET D’SOUZA

ABSTRACT

The Afghan Taliban are seemingly breaking free from their former sponsors. They have refused to accept the Durand Line as the international border with Pakistan and have failed to force the TTP to give up its violent attacks in Pakistan. Islamabad’s attempt to weaken the Taliban by driving a wedge between the hardliners’ and pragmatists’ camps has not succeeded. This compels Pakistan to reconsider its Afghan policy, seeking ways to mend fences with Kabul.

Pakistan’s Afghanistan policy is navigating rough waters. The patron-client relationship with the Afghan Taliban, envisioned by the Pakistani military establishment, was intended to create a weak state in Afghanistan and at the same time, allow Islamabad to regain the ‘strategic depth’[1] in that country. Post-August 2021, the Taliban, however, have not only failed to deliver on the expectations of Islamabad but have actually turned on their former sponsors. Despite the latter’s attempts of weakening the Taliban through fissures and factions, the divisions between the hardliners (Kandahar shura) and pragmatists (Doha shura) have not made many dents on the movement and more importantly, their view on contentious issues between Afghanistan and Pakistan. It is now up to Islamabad to unveil other strategies to ensure that its decades-long investment in the former insurgency does not go astray.

Taliban’s intransigence towards its sponsors is evident in their refusal to accept the Durand Line as the international border and continuously opposing attempts to fence the border between the two countries. The escalating border skirmishes have resulted in the killing of several Pakistani personnel by the Taliban fighters, a development which is entirely unimaginable prior to August 2021. The latest clashes occurred on 18 November at the Spin Boldak-Chaman crossing in the Afghan province of Paktia, leaving one Pakistani border guard dead. Reports from the field indicate an increasing number of such clashes.

The other serious lapse is on Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which has around 5000 to 10000 fighters in Afghan territory.[2] Islamabad had hoped that the Afghan Taliban would reign in or influence the TTP to agree to a peace deal. In the initial days, the Haqqani Network did try to broker a deal between the Pakistani state and the TTP. However, that deal as well as the one made in June this year has not lasted. On 28 November, the TTP called off the ceasefire and directed its fighters to resume attacks on the Pakistani state. Thereafter, the first suicide attack by the TTP in Balochistan on 30 November targeted security personnel guarding polio workers and killed three people[3].

The TTP’s violence is clearly on the rise and in recent times has resulted in high-profile attacks including the attack on the counter-terrorism centre in Bannu.[4] Its potential, vide its sanctuaries in Afghanistan, remains more or less intact, giving it a remote control of sorts to increase or decrease the level of violence at the time of its own choosing. According to The Khorasan Diary, a Pakistan-based news and research organization, the group has claimed 267 attacks in Pakistan between September 2021 and April 2022, including 42 in January and 54 in April.[5] An Islamabad-based think tank has also reported a 50 percent surge in terror attacks in Pakistan in the year since the Taliban took over Afghanistan.[6] The Pakistan military has relied on the Afghan Taliban to curb the TTP’s violence potential or to make it amenable for a peace deal. Neither has been fulfilled. Pakistan’s Prime Minister’s statement describing Afghanistan as a safe haven for terror groups that has miffed the Taliban is only a desperate expression of frustration.

By refusing to accept the sanctity of the Durand line and Pakistani attempts to fence the border, the Taliban are asserting their idea of sovereignty. In addition, in their symbiotic relationship with the TTP that runs both at the ideological, ethnic, and operational levels, they find a tactical pressure point to limit Islamabad’s control over Kabul. Neither is acceptable to Islamabad, which unfortunately is running out of its cards. It had hoped that the Haqqanis would be more amenable to maintaining their subservient ties with Islamabad. However, the recent developments have underlined the former’s unwillingness to rock the boat of the Islamic Emirate. The hardliners and the pragmatists within the Taliban, for the time being, appear more focused on fighting common adversaries, i.e. the Islamic State’s Khorasan Province, and the resistance groups; and working towards a common goal, i.e. seeking global legitimacy. The disinclination of Islamabad, which maintains its embassy in the country with a handful of other countries, to formally recognize the Taliban regime has not helped its own cause.

However, Islamabad is under no illusion that its ‘strategic depth’ in its original form is unachievable under the circumstances. In its conceptual form, it mostly meant subordinating Afghanistan for the purpose of Pakistan using its territory for a military redoubt in the event of being overrun by India in a conflict. Given the development of the last three decades, Islamabad can at best hope to have a friendly/cooperative regime in Kabul, nothing more.

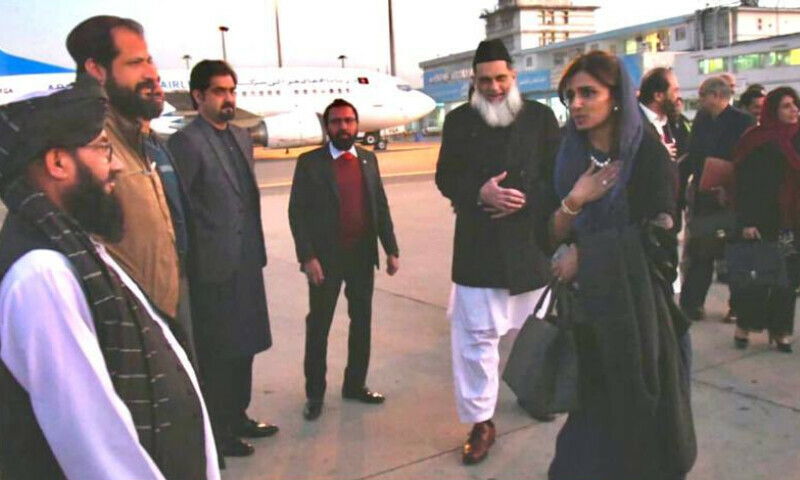

On 29 November, Pakistan rushed its deputy foreign minister Hina Rabbani Khar to Kabul for a day-long visit. Although the purpose of the visit was notified as a ‘range of bilateral issues of common interest’ by the Pakistani foreign office, smoothening the bilateral relationship and removing the irritants is high on Islamabad’s agenda.[7] She held talks with some of the regime’s top ministers and met office-bearers of a women’s business forum. Afghan media reported that Defence Minister Mullah Yaqoob rejected Pakistan’s request to meet with Ms. Khar.[8]Earlier in August 2022, Yaqoob had said that American drones entered Afghanistan’s airspace from Pakistan.[9]

The Afghan Taliban are clearly looking for avenues for image makeover to gain legitimacy not only internationally but also inside the country. This is crucial as the regime refuses to compromise on its hardcore ideology, which has resulted in decisions such as banning women from attending universities.[10] Its Pakistan policy, on the other hand, demonstrates that they are eager to shake off the image of being stooges of Pakistan. The outreach to India, especially Mullah Yaqoob’s request for India’s assistance to train troops in India[11], is another indicator of how the Taliban are trying to show independence from Pakistan. Opposing the Durand line may also help them further stoke the dream of Pashtunistan, a clear shot in their arms to gain domestic legitimacy, particularly among the Pushtuns. The subsequent developments pose a significant security and foreign policy challenge for Islamabad. The coming months would demonstrate how it plans to reset the ties to its advantage before it is a little too late.

END NOTES

[1] Aidan Parkes (2019) Considered Chaos: Revisiting Pakistan’s ‘Strategic Depth’ in Afghanistan, Strategic Analysis, 43:4, 297-309, DOI: 10.1080/09700161.2019.1625512.

[2] “Pakistan Says TTP Militants Upto 10,000 In Border Region With Afghanistan”, Outlook, 29 December 2022, https://www.outlookindia.com/international/pakistan-says-ttp-militants-upto-10-000-in-border-region-with-afghanistan-news-249152.

[3] “Pakistan Taliban claim suicide blast killing 3, injuring 28”, The Hindu, 30 November 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/pakistan-taliban-claim-suicide-blast-killing-3-injuring-23/article66203980.ece.

[4] “Hostages taken at Pakistan counterterrorism centre seized by TTP”, Al Jazeera, 19 December 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/19/hostages-taken-at-pakistan-counterterrorism-centre-seized-by-ttp.

[5] “Pakistan Saw 51% Rise in Terrorist Attacks in Year Since Taliban Took Over Afghanistan: Report”, The Wire, 21 October 2022, https://thewire.in/south-asia/pakistan-saw-51-rise-in-terrorist-attacks-in-year-since-taliban-took-over-afghanistan-report.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Khar, Taliban leadership discuss security issues and economic cooperation in wide-ranging talks”, Dawn, 29 November 2022, https://www.dawn.com/news/1723818.

[8] “Afghan defence minister Mullah Yaqoob refuses to meet Khar?”, Daily Times, 30 November 2022, https://dailytimes.com.pk/1033565/afghan-defence-minister-mullah-yaqoob-refuses-to-meet-khar/.

[9] “Taliban accuses Pakistan of allowing US drones in Afghan airspace”, Al Jazeera, 28 August 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/8/28/taliban-accuses-pakistan-of-allowing-us-drones-in-afghan-airspace.

[10] “Taliban says women banned from universities in Afghanistan”, Al Jazeera, 20 December 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/20/taliban-says-women-banned-from-universities-in-afghanistan.

[11] “Taliban willing to send Afghan troops to India for training: Mullah Yaqoob”, News 18, 2 June 2022,https://www.news18.com/news/world/great-expectations-of-india-gave-crucial-help-in-past-afghan-defence-minister-to-news18-global-exclusive-5292811.html.

(Dr. Shanthie Mariet D’Souza is Founder & President, Mantraya and Visiting Faculty, Naval War College, Goa. She has conducted field research in Afghanistan and Pakistan for more than a decade. A shorter version of this article appeared as an Oped in the Hindustan Times on 27 December 2022. This Policy Brief has been published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Mapping Terror & Insurgent Networks” and “Fragility, Conflict, and Peace Building” projects. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)

To read previous Mantraya Policy Briefs CLICK HERE