MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#59: 06 AUGUST 2022

Myanmar Military’s Annihilation Strategy: The Future of Democracy

BIBHU PRASAD ROUTRAY

ABSTRACT

Ongoing armed contestations between the military junta in Myanmar and the civilian armed groups demanding restoration of democracy are nearly a year and a half old. The military’s initial assessment of quelling the opposition swiftly has been proved wrong. Pitted against a determined opposition of PDFs and EAOs, the junta has resorted to a strategy of annihilation, supported by countries like Russia and China. On the other hand, the unfolding of events and endemic violence perpetrated by the junta is being watched rather helplessly by the international powers and regional and international organisations, with periodic condemnations and little else. The junta fancies its chances of eventually crushing the opposition and democracy in the country.

Introduction

Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military), which rules the country in the name of the State Administrative Council (SAC), does not shy away from drawing red lines. These include how much democracy will it allow flourishing, how much curtailment of its own power will it tolerate, and how much expression of dissent can it condone. It’s every action, ever since it reluctantly started loosening its control over the political process in the early 2000s, has been guided by considerations of survivability. While nearly a decade of experiments with democracy had raised hopes for further progress, it was evident that the growth of liberal democracy in the country would not only be constrained but could be reversed the moment the Tatmadaw perceives a danger to its paramountcy. Hence, the February 2021 coup that upended the results in the 2020 parliamentary elections and the ruthless stabilisation project undertaken since then by the Junta are parts of its strategy to remain relevant, powerful, and the ultimate arbitrator of Myanmar’s body polity.

On 25 July, the Tatmadaw executed four democracy activists, after they were sentenced to death in a closed-door trial. All four, including activist Ko Jimmy and former member of parliament Phyo Zeya Thaw, had been convicted of ‘terrorism’, a phrase the junta has conveniently used to describe activities centered on restoring democracy in the country. While these executions, the first in at least three decades in Myanmar, can be considered a new low in the Tatmadaw’s war on the pro-democracy activists and have evoked shock and anger across Myanmar and have been condemned by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and several countries, such sanctioned annihilation of dissenters need to be contextualized within the Tatmadaw’s age-old strategy of quelling dissent.

The future of democracy in Myanmar, therefore, remains linked with the Tatmadaw’s capacity to orchestrate violence as well as its perceived sense of impunity. While the Tatmadaw’s history is replete with waging unending wars against its own people, past months have demonstrated that such capacity to target the opposition can falter unless reinforced by external sources. This analysis attempts to bring to focus the multiple sources behind such strength which fuels the Tatmadaw’s annihilation strategy. It also underlines the strengths and vulnerabilities of the opposition. The analysis argues that as long as the SAC continues to be empowered by external sources, it will fancy its chances of getting away with mass-scale human rights abuses and may even succeed in crushing democracy in Myanmar permanently.

Endemic Violence

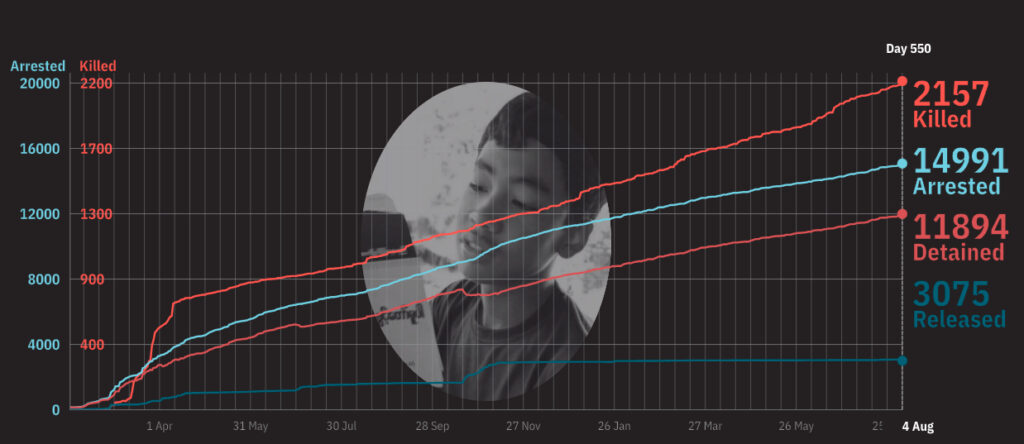

Since orchestrating the coup on 1 February 2021, the Tatmadaw has implemented a two-prong strategy against pro-democracy politicians and civilian activists. One of these is political and legal. 14970 people, including politicians and activists, remain in detention for opposing the military’s seizure of power, according to the rights group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP).[1] 117 people, including two children, have been sentenced to death. Of them, 41 have been sentenced in absentia. A large number of legal cases pertaining to accusations of corruption and electoral fraud have been filed by the Tatmadaw in courts against former state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, where she gets periodically convicted with multiple sentences. The strategy of targeting Suu Kyi, former ministers and office bearers of the deposed civilian government, and her several colleagues from the National League for Democracy (NLD) seem to be to drive them to a point of political redundancy.

The macabre and grotesque, however, continue to take place on the second level. The wrath of the military has been unleashed on the hundreds of People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), the civilian armed resistance groups country and some of the Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) in the periphery, who have trained them. In the initial months, soldiers of the Tatmadaw were in charge of the campaign against the PDFs and the EAOs. Subsequently, however, mostly to fill in the vacancies by deserting soldiers and police personnel, a large number of militia groups have been created by the Tatmadaw. As a result, Pyusawhtis (paramilitary militias) and the shadowy Thway Thauk Apwe pro-military groups have become an integral part of the official scorched earth policy. The military has also recruited a large number of Anghar-Sit-Thar (hired soldiers), paying them a monthly salary of approximately US$100. These groups, consisting of disposable and largely untrained fighters, have not only economized the military’s war efforts but with a mandate to burn villages, loot, kill and torture civilians, and rape women, have wreaked havoc in the EAO-dominated areas, which shelter many PDFs.

In a conflict-ridden country, where ground-level reporting is either difficult or largely unverifiable, Planet Labs and Google Earth images bear testimony to vacated and burnt villages. On rare occasions, deserter soldiers have narrated how they were ordered by their commanders to round up and kill innocent people. The military has supplanted its ground-level weakness by using attack helicopters to open aerial fire. Such unceasing hostility has resulted in the internal displacement of 700,000 and mass casualties. A group of open source researchers tracking human rights abuses, named Myanmar Witness, has verified more than 200 reports of villages being burnt between September 2021 and May 2022 in the north-west Sagaing and Magway region, allegedly in retaliation for their support to PDFs and the National Unity Government (NUG), the shadow government of the ousted civilian administration. The increasing intensity of such attacks is clear from the fact that 146 of these incidents have taken place between January and May 2022.[2]

In December 2021, nearly 35 people including a child were killed after army troops deliberately set the people in the trucks on fire using gasoline as an accelerant in Kayah state, suspecting them to be the sympathizers of the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force (KNDF), an insurgent group which has pledged support to the NUG. In July 2022, at least 10 villagers were killed during a military raid on a village in the Sagaing region.[3] Scores have been killed in unreported night raids, secret assassinations and targeted annihilations. According to the United Nations human rights chief Michelle Bachelet, “over 30 percent of over 2,100 people killed since February 2021 have died in military custody – most as a result of ill-treatment.”[4] The junta’s intention of silencing even an iota of protest in the most depraved manner is no longer a matter of debate.

Junta’s Sense of Impunity & Specter of Civil War

The Tatmadaw legitimizes its violent campaign as aimed at the ‘terrorism’ perpetrated by the PDFs and the EAOs, and has vowed to annihilate them.[5] It has declared its intention of bringing peace and stability to the country before holding another round of elections to elect a new government. And yet, there is little reason to believe such false claims and assurances, as it continues to extend the state of emergency[6] imposed in the country.

The Junta’s manpower strength is unknown, with estimates varying from 250,000 to 350,000. The actual number of combat soldiers is far lower—in the range of 80,000 to 120,000. The National Police force is around 80,000 strong.[7] As mentioned earlier, it has been able to add more manpower by enlisting militia members, pro-military groups as well as hired mercenaries. This gives it a tactical advantage vis-a-vis the PDFs and the EAOs. However, the real power behind continuing with its campaign comes from two sources: indifference shown by the regional as well as global powers to the rampant human rights violations by the Junta and the latter’s continuing ties with the military hardware-providing countries such as China and Russia.

Barring repeated statements condemning the Myanmar military, unveiling sanctions against key military figures, and demanding that the democratic process be restored in the country major powers such as the United States and the United Kingdom have done little to bring pressure on the Tatmadaw. The United Nations, time and again, has condemned the Junta for committing war crimes and crimes against humanity. It has retained Kyaw Moe Tun, appointed by the deposed civilian government, as the Permanent Representative of Myanmar. And yet, preoccupation with the Ukraine war has pushed Myanmar out of the priority list of most major powers.

The 10-member ASEAN admitted Myanmar into its fold in 1997. However, as an organization that uses the ‘consensus’ as an operating principle, ASEAN has demonstrated its concern, aloofness, and helplessness— all at the same time— to Myanmar’s ‘internal issues’. Few months after the coup, in April 2021, army chief Min Aung Hlaing was invited to a specially-convened ASEAN meeting in Jakarta where a five-point consensus to end the violence and help resolve the crisis was agreed on. Upon return home, Hlaing refused to implement it. In response, the ASEAN refused to include Myanmar in its subsequent summits. At the same time, however, Myanmar’s defence minister General Mya Tun Oo participated in the annual ASEAN Defence Ministers’ meeting in June 2022. The ASEAN special envoy, Cambodia’s deputy prime minister and foreign minister, Prak Sokhonn, during his two trips to Myanmar, was denied access to Aung San Suu Kyi. During the June 2022 trip, Min Aung Hlaing reportedly told him that meeting Suu Kyi “was not yet possible” but that it could happen “maybe at a later stage”[8]. On 20-21 July, Russia and Myanmar co-chaired the 13th ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM)-Plus Experts Working Group (EWG) on Counter-Terrorism in Kubinka, near Moscow. The meeting was boycotted by the US, Australia, and New Zealand, but attended by all ASEAN members.[9]

Japan, a member of the Quad along with the US, Australia, and India, has continued training the Myanmarese defence forces in its National Defense Academy and the Air Self-Defense Force Officer Candidate School. Australia has suspended military cooperation with Myanmar and redirected foreign aid away from the SAC, as well as throwing its diplomatic weight behind ASEAN’s efforts to resolve the crisis. At the same time, the Australian embassy in Yangon has been accused of spending over US$525,473 with the Junta-linked Lotte Hotel and Lotte serviced apartments in Naypyitaw since February 2021 coup. In June 2022, the deputy leader of an Australian cross-party committee that scrutinized the country’s political and diplomatic response to the Myanmar crisis termed it ‘constipated’[10]. India was among the eight countries which participated in the Tatmadaw’s Armed Forces Day celebrations in March 2021. It also ordered the deportation[11] of Myanmarese refugees who had crossed over into Indian territory. New Delhi hopes to elicit Tatmadaw’s cooperation against the insurgents operating in its northeast region, with bases in the Sagaing region. Yet, media reports indicate[12] that the Tatmadaw could be using the same insurgents against the pro-democracy activists.

Preventing a full-scale civil war situation in Myanmar and pursuing their own national interests are among the factors, which influence decision-making in individual countries. These may have indirectly added to the strength of the Tatmadaw and legitimized its actions. Of more direct assistance to the Tatmadaw are China and Russia, who have not only protected the Myanmar military from censorship in the UN on multiple occasions but continue to provide it with military hardware, which ostensibly is being used against the PDFs and EAOs. China’s links with the Tatmadaw have a long history. In the past years, however, the Tatmadaw has attempted to diversify its military hardware procurement sources by reaching out to Russia. SAC Chairman Min Aung Hlaing has made multiple trips to Moscow. In his week-long trip in July 2022, Aung Hlaing met the director general of Russian state energy company Rosatom and signed an MoU to cooperate on skills development in nuclear energy in Myanmar.[13] The development of nuclear energy in Myanmar may be too far-fetched, but the MoU does indicate deepening Myanmar-Russian bilateral relations. Russian support to the Myanmar Air Force (MAF)—by recently providing it with two Su-30 Fighter Jets and a Mi-24P attack and transport helicopter, and also by stationing a technical assistance team in Myanmar to train and assist the MAF —has proved to be a key enabler in the latter’s air raids on the EAOs and PDFs.

The Opposition: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Challenges

In early 2022, the Tatmadaw chief indicated that he could have underestimated the power of the opposition. Over 200 PDFs operate in Myanmar’s urban centres, and Sagaing and Magwe regions. The NUG, to which the PDFs pledge their support, claims control over 15 percent of the country’s territory. Combined with another 30 to 35 percent over which the EAOs have dominance, half of Myanmar’s territory is effectively out of the purview of the Tatmadaw. Attacks, with growing sophistication, are regularly carried out by PDF fighters against the military’s regime and its benefactors. The armed resistance has been hailed as a stupendous example of unity among the majority Bamar population and the ethnic groups by analysts. Since the February 2021 coup, over 2500 army and police forces have deserted and are reportedly with the opposition. Such assessments and number crunching, while holding a beacon of hope for the pro-democracy-movement, do little to hide its vulnerabilities, mostly at the operational as well as logistical levels.

The NUG has sought to raise US$1 billion to sustain its operations including supporting the PDFs. However, without external financial support, it is falling back on innovative methods to raise finances internally as well as from the expat Myanmar nationals and other concerned persons/entities. Funds collected outside of Myanmar are either being channeled unofficially or through cryptocurrencies into the country, to avoid the Junta-controlled banking system.[14] However, as the war continues, the NUG will have to explore other financial sources to sustain its operations.

The European Parliament[15] and French Senate[16] have recognized the NUG as Myanmar’s only legitimate government. The US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has tweeted support. However, the NUG and the PDFs require material support in addition to such pledges. The Tatmadaw uses Russian and Soviet-era choppers not only for maintaining supply lines, troop deployment, and evacuations but also for attacking the PDFs and EAOs. The latter neither have access to any choppers of their own nor have any advanced missile systems to bring down these military flying machines. Unless the PDFs receive significant external assistance, in terms of funds, arms, and expertise, their ability to threaten Tatmadaw’s position would always remain limited.

To compel Tatmadaw to accept their demand, the EAOs and PDFs will have to widen the area of operations far beyond the Sagaing and Magwe regions. Unless the theatre of conflict is expanded, the Tatmadaw will not only have the advantage of carrying out focused area operations, but it will also be able to absorb the recurrent, and yet middling damages inflicted by the opposition. So far, the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), are working with the NUG and fighting alongside resistance forces against Tatmadaw’s troops. Some other EAOs have either unofficially supported the NUG or have remained uncommitted. Extracting active support from a majority of the 20 EAOs operating in the country would be necessary for the NUG in the coming months.

So far, the PDFs have done exceedingly well against the troops. Although figures of fatalities among the troops in attacks by the PDFs may have been inflated, it remains a fact that battlefield skirmishes and surprise attacks have created an atmosphere of fear among the superiorly trained troops. Due to the recurrent attacks on official installations and police stations, Yangon has been labelled as the most dangerous city in Myanmar.[17]However, sustaining such attacks, in the long run, may prove to be a challenge. Paradoxically, too much of violence unleashed by the PDFs may also make them unworthy of receiving any assistance from external sources.

Two-prong strategy: Tilting the Balance?

Insurgency movements or armed uprisings against a conventional military force have rarely succeeded without significant external support. Belief in principles and conviction in a cause can prolong the life of such uprisings, but do not add to their winning probability against an adversary pursuing a strategy of annihilation. Insurgency movements of Myanmar have a prolonged history of confrontation with the Tatmadaw, stretching over several decades. They have mostly remained undefeated, carving out and ruling over near-autonomous homelands. But for the PDFs, the goal is much larger. Toppling a shadow government of the military or coercing it to send its soldiers back to barracks and restore power to the NLD is a far more difficult task.

Currently, neither Tatmadaw nor the armed opposition is willing to accept defeat. International and regional powers, apprehensive of a full-blown civil war situation at the heart of Asia, are averse to materially assisting the NUG and the PDFs. The stalemate, therefore, is a recipe for continued conflict, tilted in favour of the military. In the coming months, the Tatmadaw may continue pursuing a two-prong strategy of increasing the scale and sweep of its operations and trying to avenge its battlefield losses by persecuting softer targets, i.e. the imprisoned politicians and the activists. International condemnation of the July 2022 executions of the four activists may prevent further prison executions but will do little to deter Tatmadaw from further pursuing its annihilation strategy.

End Notes

[1] Data till 3 August 2022. See website of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, https://aappb.org/.

[2] Myanmar Witness, Burning Myanmar, 22 July 2022, https://www.myanmarwitness.org/reports/burning-myanmar.

[3] “Myanmar villagers accuse junta troops of massacre”, The Straits Times, 22 July 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/myanmar-villagers-accuse-junta-troops-of-massacre.

[4] United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Myanmar: Bachelet condemns executions, calls for release of all political prisoners”, 25 July 2022, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/07/myanmar-bachelet-condemns-executions-calls-release-all-political-prisoners.

[5] “Myanmar junta chief vows to annihilate opposition forces”, CNN, 28 March 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/28/asia/myanmar-min-aung-hlaing-annihilate-opposition-intl-hnk/index.html.

[6] Frances Mao, “Myanmar military extends emergency rule until 2023”, BBC, 1 August 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62373975.

[7] Andrew Selth, “Myanmar’s military numbers”, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, 17 February 2022, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/myanmar-s-military-numbers.

[8] “ASEAN special envoy plans third trip to Myanmar; hopes to use Aung San Suu Kyi’s influence to end violence”, Channel News Asia,20 July 2022, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/asean-envoy-sokhonn-myanmar-aung-san-suu-kyi-2823506.

[9] Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, Meeting of ADMM Plus expert working group on counter-terrorism took place in Moscow region, 20 July 2022, https://eng.mil.ru/en/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12429797@egNews.

[10] “Government urged to consider sanctions against Myanmar military and permanent residency for nationals”, ABC News, 24 June 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-24/australia-sanction-myanmar-military-permanent-residency-report/100240686.

[11] “Home Ministry Asks Border States In Northeast To Deport Myanmar Refugees”, NDTV, 12 March 2021, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/home-ministry-asks-border-states-in-northeast-to-deport-myanmar-refugees-2389684.

[12] Mohamed Zeeshan, “India Needs to Get Real About the Instability in Myanmar”, Diplomat, 21 January 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/01/india-needs-to-get-real-about-the-instability-in-myanmar/.

[13] “Myanmar seeks Russian assistance in push for nuclear energy”, Nikkei Asia, 19 July 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Myanmar-Crisis/Myanmar-seeks-Russian-assistance-in-push-for-nuclear-energy.

[14] “Inside the global drive to fund a revolution in Myanmar”, Japan Times, 23 February 2022, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2022/02/23/asia-pacific/myanmar-funding-revolution/.

[15] “European Parliament Throws Support Behind Myanmar’s Shadow Government”, Irrawaddy, 8 October 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/european-parliament-throws-support-behind-myanmars-shadow-government.html.

[16] “French Senate recognises Myanmar National Unity Government”, ITUC, 6 October 2021, https://www.ituc-csi.org/french-senate-recognises-myanmar.

[17] “Myanmar Regime’s Executions of Activists Make Yangon Even More Dangerous”, Irrawaddy, 29 July 2022, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-regimes-executions-of-activists-make-yangon-even-more-dangerous.html.

(Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray is Director of Mantraya. This analysis has been published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Mapping Terror & Insurgent Networks” and “Fragility, Conflict, and Peace Building” projects. A shorter version of this article was first published in ‘Conflict Weekly’ of the NIAS, Bangalore on 5 August 2022 under the title ‘Myanmar Military: Annihilation as a Domination Strategy‘. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)

To read previous Mantraya Analyses CLICK HERE