MANTRAYA OCCASIONAL PAPER #06: 12 MARCH 2018

Pakistan-based militant groups & Prospects of their integration: A Structural Analysis

–

Muhammad Amir Rana

–

Abstract

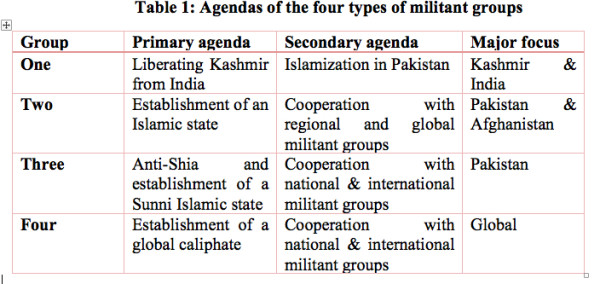

Different militant streams operating in Pakistan are characterized respectively by conventional jihadist groups – established to safeguard the state’s strategic interests in the region; independent militant groups – formed by the militants who grew in the folds of or parallel to conventional groups but gradually formed their separate groups such as tribal Taliban militant groups; violent sectarian groups and new militant groups/cells as well a self-radicalized individuals; and foreign militant groups such as Al-Qaeda, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and the Islamic State. Although all these four groups or categories have diverse primary, or priority agendas – ranging from liberating Kashmir to targeting Shias and establishing national and global Islamic state or caliphate – but almost all share similar secondary agendas which include cooperating with global militant groups. The conventional groups have developed expansive physical infrastructure and assets which some see as their weakness that does not allow them to go against state. Meanwhile, collaborations and nexus among groups play an important role in determining the operational strength of a group. Without breaking this operational nexus, preventing major guerrilla-style terrorist operations would be an uphill task. The reintegration prospects, though, can be explored within the conventional militant groups, who appear willing to be part of political mainstreaming.

Introduction

Pakistan’s militant landscape is quite diverse including in terms of ideological shades and outreach as well as its links to the larger religious and religious-political discourses in the country. That makes it much more difficult to assess the potential threats this landscape offers and ascertain prospects of militants’ disengagement from violence and violent groups and eventual reintegration into society.

Populated with militant groups formed during the Soviet-Afghan war, the country’s current militant landscape is also characterized by the terrorist groups, and in some instances even small cells, which have appeared in recent years. Many of these militant groups’ ideological and political aspirations overlap but each group tries to achieve those aspirations in a distinct and at times exclusive manner, which keeps them on different courses.

Most of the militant groups in Pakistan operate underground, though some are quite visible on the surface, but only through their welfare and charity wings, which create ambiguity in the minds of the people about these groups’ militant credentials. Although the latter are not involved in terrorist activities in Pakistan, their breakaway factions and individuals once associated with them have facilitated and empowered Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Al-Qaeda, and other militant groups in Pakistan and Afghanistan, including those targeting Pakistan.

Some of these groups are also trying to become part of the political far-right in Pakistan by gradually detaching themselves from anti-state militant organizations. For instance, the banned Jamaat-ud Dawa (JuD) is projecting a new political face, the Milli Muslim League (MML), as an alternative model to challenge the ISIS and Al-Qaeda ideologies. The group believes that its ideological ambitions resonate with those of Pakistan and that an Islamic ideological transformation of the Pakistani state and society will not only reduce the appeal of Islamist militant organisations but will also help engage the youth in ‘constructive’ activities.[1]

These and similar other political and ideological changes in the militant landscape are reshaping the character of all three generations of militants – i.e. which emerged during Soviet-Afghan war; after the 9/11 incidents; and most recently, during and after the 2007 Red Mosque siege in Islamabad. These in turn are also transforming the militant groups.

The situation thus requires a structural analysis of the militant groups operating in Pakistan with a view to better understand their politico-ideological transition, national and global viewpoints which include their goals and agendas, strategies to achieve those objectives and also prospects of these groups’ or individuals’ disengagement from violence and reintegration into society.

To start with, the following analytical framework can help understand the dynamics of the militant groups in Pakistan in a much proper and effective way.

The militant groups usually have very broad objectives and their manifestos give the impression that they want to bring about a global revolution. But in practical terms their areas of operations remain confined to narrow territorial frameworks, which raises the following questions, which are elementary and could help assess the true operational potential of the militant groups.

- Do these groups really harbour ambitious militant objectives and targets? Or is this part of their rhetorical propaganda campaigns to expand their ideological and political appeal among the masses?

- Do their written objectives, verbal rhetoric, ideological tendencies, operational priorities and organizational strengths are mutually harmonized?

- Is it part of their tactical approach to concentrate on immediate challenges first and gradually expand their operations subsequently?

Varied forms of militant groups, with a range of ideological and political tendencies are operating in Pakistan. These groups have many similarities, but it is important to consider what makes them different and where their interests converge. Equally important is to probe how these groups influence each other and how they broaden their ideological paradigms. In many cases, militant groups combined their resources for achieving certain objectives. It is important to determine the strength and lifespan of such alliances. After analyzing the aspects cited earlier, probabilities for effective engagement with the militants can be drawn, and spaces identified to intervene in order to break the cycle of terrorism. Most importantly, the prospects for reintegration of militants can thus be explored.

It is useful to understand the three streams of militancy in Pakistan that shape the prevalent militant landscape.

1. Streams of militancy in Pakistan

1.1 Conventional groups

Though these groups are not involved in terrorist activities in Pakistan, their breakaway factions have been providing human resource to anti-Pakistan local and foreign militant groups such as Al-Qaeda, tribal militants of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and its factions, and most recently, the ISIS. Some of them, in an effort to become part of far-right politics in Pakistan, are gradually detaching themselves from the swarm of anti-state militant groups.

The conventional groups were established in connection with the Soviet-Afghan war in the 1980s and later their operational scope was expanded to fight in Kashmir. The establishment of these groups was aimed at fighting proxy wars for the Pakistani state and to safeguard its strategic interests in the region. Their ideological foundation rested on religion and Pakistani nationalism, i.e., an identity and ideology of Pakistan based on the two-nation theory that was used to demand separation from Hindus. They believe that the merger of Kashmir with Pakistan would be the eventual culmination of the country’s independence movement. Jamaat-ud Dawa (JuD) goes a step further and demands the merger of the princely states of Hyderabad and Junagadh too with Pakistan, arguing that both states had announced their annexation to Pakistan after the partition of India in 1947.

When, after 9/11, some conventional militant groups decided to fight alongside the Afghan Taliban against the international coalition forces in Afghanistan, Pakistan’s security establishment realized for the first time that religion was an area where it could not be certain of its control over these groups. Pakistan banned many of these groups under international pressure on 13 January 2002, and some others on 16 November 2003. Facing internal crises and external pressure, leadership of such groups was either arrested or went underground, causing further rifts among the lower-rung cadres, who gradually started fleeing to the tribal areas and joined tribal Taliban and foreign terrorist groups based there.

Many of these groups subsequently resurfaced with different names and under the garb of charities. This ploy not only helped them gain social acceptance but also enabled them to expand their support base and ultimately add to their financial resources. In an attempt to diversify their assets, some militant groups set up commercial ventures such as English-medium schools, healthcare centres, transportation companies, residential projects and media groups; some also acquired farmland on a large scale.[2]

1.2 Independent groups

Independent militant groups can be classified into three major sub-categories: tribal militant groups; violent sectarian groups; and new militant groups/cells.

- Tribal militant groups

The tribal militant groups are a post-9/11 phenomenon. Though the tribal militants were present among the Afghan and Pakistani militant groups during the Soviet-Afghan war and the Kashmir insurgency, they did not have their own independent groups.

In October 2001, the Taliban and Al Qaeda operatives moved into Pakistan’s tribal areas. Initially concentrated in the South Waziristan tribal region, they expanded their existing support base which are rooted in the cross-border connections going back to the 1980s and ethnic linkages among the local tribes.[3] There was a wave of sympathy for the Taliban among the local population as they were seen as having been ousted by an invading power. Using this support, between 2002 and 2004, these Afghan groups organized scattered militants, developed a nexus with local tribesmen, and waged extensive guerrilla operations against coalition forces in Afghanistan until Pakistani forces began concerted operations against them in February 2004.

However, very little suggested that a small local militant movement in the tribal areas would become a full-fledged insurgent movement until a peace deal, known as the Shakai agreement, was reached between a Pakistani militant leader Nek Muhammad and the Pakistan military on 27 March 2004 in South Waziristan. The deal empowered the local militants, who later declared themselves the Pakistani Taliban, to enforce their writ in the area. The government had agreed to pull its troops out of the tribal areas, and to release all the individuals arrested during security forces’ operations. In return, it received the assurance that the tribes would not allow the use of their territory against any other country, mainly the NATO forces in Afghanistan.[4] In his address on the occasion of the agreement, Nek Muhammad had declared that they did not want to challenge the writ of the state but would take up arms against it if they were persecuted.[5]

Until 2004, the main focus of the Pakistani Taliban was to protect foreign militants, recruiting and training them for the war in Afghanistan, and securing their position against security operations. What transformed them into a major player in FATA was a tactical change in their operations: they began kidnapping security and state officials from 2004. Although suicide attacks on security forces started in 2006-07, the kidnapping strategy elevated the Taliban to a position where they compelled the state to negotiate on their terms. Over time, this became one of the Taliban’s most rewarding strategies. Independent sources estimate that the Taliban kidnapped more than 1,000 security forces, personnel, and state officials in 2007, with over 500 militants being released in exchange for their return.[6]

The Shakai agreement was not honoured by either side, which resulted in another military operation in South Waziristan in April 2004. It was the first time that the militants waged a massive campaign against the army in South Waziristan and got local clerics to issue fatwas (religious decrees) declaring Pakistan to be Darul Harb (literally, a territory of war) — a land where Muslims could not live with personal security or religious freedom.[7] Economic sanctions imposed on tribes by the authorities further fuelled anti-state sentiment and paved the way for the militants to develop parallel systems in the areas where they held sway.

The commanders of militants from the Wazir tribe led by Mullah Nazir reconciled with the situation and preferred to focus on Afghanistan. Lashkar-e-Islam in Khyber Agency of FATA was earlier a sectarian organization but it followed the Pakistani Taliban’s modus operandi, which helped the group sustain its hold in the agency. Later, it became a support group for the TTP.[8]

Baitullah Mehsud had united various tribal militant groups under the banner of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in 2007. He was killed in a US drone strike in South Waziristan in August 2009. The TTP remained a critical Taliban force from 2007 to 2014 though with varying degree of influence. It established its chapters in different agencies of FATA, Balochistan and Karachi. At a time, in 2007, it had become such a formidable force that it had established a virtual state in parts of Swat with support from its Punjab-based and international terrorist groups. The Swat operation in 2009 and the Zarb-e-Azb operation in 2014 in North Waziristan significantly dented the group whose leadership is largely believed to be hiding in Afghanistan along with its splinter groups such as Jamaatul Ahrar and Mehsud Taliban, or Sajna Group. Mullah Fazlullah, previously head of TTP’s Swat chapter, currently heads the group. Indeed, internal factionalism – the TTP was originally an alliance of over 40 groups – and infighting over leadership, mainly after the death of Hakeemullah Mehsud in a drone strike in 2013, also weakened the group besides the military operations.

- Violent sectarian groups

Violent sectarian groups in Pakistan have proven to be strategic assets for foreign and tribal militants. These groups have networks and extensive support bases inside Pakistan and provide human resources and operational support to these groups in launching terrorist attacks. These also serve as tools in the hands of the TTP, Afghan Taliban and the Haqqani Network in bargaining with Pakistani institutions.

Many of the banned sectarian organizations wear political hats and take part in electoral politics, even if they do so under different names or by having their candidates run as independents or by making alliances with the mainstream political parties. These groups gain political legitimacy through these practices.[9]

Once a breakaway faction of the sectarian Sunni group Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), now known as Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ), the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) has an extreme violent anti-Shia agenda. While claiming to be a separate entity, it continues furthering the cause of the SSP or ASWJ in one way or another. The group depends on the SSP for human resources and justifies the killing of Shias in Pakistan. A small and insignificant faction within the SSP is against sectarian violence.

The LeJ had its lost central command when the police launched an extensive operation against the group in the late 1990s and later with its proscription in August 2000. These steps caused fissures within the group and led to the emergence of many splinter groups. A recently revived faction calls itself Lashkar-e-Jhangvi Al-Alami (LeJ-A) or LeJ-Global and has claimed responsibility for some major terrorist attacks in 2016-17.

After 9/11, LeJ terrorists had joined the disgruntled Kashmiri jihadists, who were upset with the sudden change Pakistani state’s policy to abandon jihad in the region. The nexus was further strengthened when these small groups joined Al-Qaeda and the tribal Taliban. This emerging alliance was behind almost all the major terrorist attacks in Pakistan between 2001 and 2007. Such alliances ideologically transformed the sectarian groups, injecting in them global jihadist tendencies. This was the time when the LeJ had become a tag name for small terrorist cells. Qari Hussain, a notorious trainer of suicide bombers who was killed in a drone strike in 2010, had infused new life into the group by recruiting Punjab- and Karachi-based youth and re-initiating sectarian terrorist attacks. Tariq Afridi, head of the TTP’s Darra Adam Khel chapter, was the second person who revitalized the violent sectarian agenda of Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and launched deadly terrorist attacks in FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

However, on the organizational level the LeJ has remained splintered in recent years. The Balochistan chapter of LeJ, led by Usman Kurd,[10] which targeted the Hazara Shia community in Quetta, had little interaction with factions in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Seven other LeJ groups are present in Karachi and Punjab, though much weakened now, including the Attaur Rehman alias Naeem Bukhari, Qasim Rasheed, Muhammad Babar, Ghaffar, Muaviya, Akram Lahori and Malik Ishaq groups.[11] These groups have devised their local agendas as well and indulge in local turf wars.

Some Shia and Barelvi violent sectarian groups also operate in Pakistan, but they fall in the category of reactionary groups, and do not have extensive connections with global and regional terrorist groups.

- The new militants

This is a comparatively new stream, which includes multiple types of militant groups and small terrorist cells. It mainly comprises breakaway factions or individuals of the two streams discussed earlier as well as self-radicalized individuals including on cyberspace. The Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS), brands of Punjabi Taliban, separate Jundullah groups in Sindh and Balochistan provinces, Ansarul Shariah in Karachi, and ISIS-inspired terrorist cells, etc., constitute this militant stream.

The term ‘Punjabi Taliban’ refers to militant and sectarian outfits — or their breakaway factions — which once were operating in Kashmir and Afghanistan or had been involved in sectarian violence in Pakistan. The Punjabi Taliban had emerged out of the militant and sectarian landscape of Pakistan and shared a similar worldview, ideology and political and sectarian ideas.

Yet, these groups demonstrated some distinguishing features. First, they detached themselves from their parent militant organizations over multiple strategic and tactical differences, mainly after describing the leaders of their parent organizations as puppets of state intelligence agencies. The Punjabi Taliban thus acquired complete freedom from official control and maintained that they were following the true path of ‘jihad’. This was despite the fact that the conventional groups opposed terrorist activities inside Pakistan.

Secondly, the Punjabi Taliban had borrowed their political narrative from Islamist political parties but had been following Al-Qaeda’s takfiri ideology, despite the fact that they were not formally affiliated with transnational militant groups or Islamist political parties operating in the country. Overall, the Punjabi Taliban phenomenon ushered in a new approach in the name of religion in Pakistan.[12]

The phenomenon of Jundullah is important in the context of urban militancy. In the same manner as there are many Punjabi Taliban groups, many groups are also operating under the Jundullah nomenclature in Pakistan. While the Punjabi Taliban emerged from Deobandi and Salafi militant groups, the Jundullah groups are breakaway factions of the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and its student and militant wings.

With the exception of Jundullah in the Iranian Baluchistan-Sistan region – which has largely nationalistic credentials and whose militants, Iran asserts, operate in Pakistani-Iranian border areas including in Pakistan’s Balochistan province – the remaining entities under this label, active in Karachi and the Peshawar valley, are of a similar disposition. With their Islamist background, they are naturally inclined towards the Islamic State militant group and like a few commanders of the Hizb-e-Islami — a JI-affiliate in Afghanistan — apparently intend to announce their allegiance to ISIS.[13]

Militants in the making are a dangerous phenomenon of this stream. Self-radicalized individuals fall in this category. Though not formally affiliated with any local or international terrorist organization, they are in search of causes that resonate with their radicalized worldview. The numbers of potential militants in this category could be large. A failure to find and join a ‘proper’ terrorist group can encourage them to plan and launch terrorist attacks by defining the targets themselves.[14] Many religious scholars and madrassa teachers consider this segment of potential militants quite crucial as they are an important source of recruitment for militant organizations.[15]

This threat of these self-radicalized individuals is not new and can be understood by examining the emergence of the Punjabi Taliban during the Red Mosque operation in Islamabad when militants of conventional groups started leaving their groups to join the TTP and Al-Qaeda. Self-radicalized youths had also formed small terrorist cells at that time. Many of these groups or individuals did not succeed in joining any terrorist group but were found involved in planning terrorist attacks on their own. Such small groups were quite active in Islamabad, Rawalpindi and Lahore and carried out small-scale attacks on cultural sites, girls’ schools and posh markets during 2008-2010.[16]

1.3 Al Qaeda, ISIS and foreign groups

The foreign militants – mainly Al-Qaeda, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and ISIS – played an important role in transforming Pakistani groups and their dynamics. Al-Qaeda, in particular, came up with an ideological and political agenda, which appealed to Islamist militants in countries all over the world.

The Pakistani Taliban’s main strength had been their ideological bond with Al-Qaeda and their connection with the Islamization discourse in Pakistan. They gained political and moral legitimacy by associating with the Afghan Taliban. Their tribal and ethnic ties provided social space and acceptance among a segment of society.[17]

Similarly, the breakaway factions of conventional groups became invaluable assets for Al-Qaeda as their objectives converged. The Taliban absorbed both tendencies and became agents of change in their respective areas. They felt empowered in a system where tribesmen had been the victims of colonial-era laws, political agents and maliks.

An operational nexus between foreign and local militant groups made both more lethal. A review of some of the high-profile attacks carried out in Pakistan suggests that four major militant formations acted in different phases to carry out these attacks; Al-Qaeda planned and strategized, the TTP provided logistic support, IMU served as operational core, and one local militant group or another facilitated the attacks on the ground.[18] ISIS inspires many militant groups in Pakistan, posing a real emerging threat.

2. A SWOT analysis of the militant groups in Pakistan

Apart from the different streams of militancy described earlier, militants in Pakistan can also be divided into three generations, which may overlap in some of the previously cited streams. The first generation of militants, largely falling in conventional stream, comprises those jihadis who were nurtured post-1979 to fight the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and onward into the 1990s. The second generation militants started to emerge towards the end of the 1990s but acquired more clarity and organization after the 9/11 episode. These were the middle and lower rungs of militant groups disillusioned with their leaderships whom they saw as compromising on religious ideals for the sake of expediency. The third generation militants are mostly self-radicalized individuals belonging to the educated middle class.[19]

Based on these trends and depictions, the militant group in Pakistan can be divided into four broader categories for the purpose of their structural analysis.

- Group One consists of conventional militant groups, and militants from the first generation belong to this category.

- Group Two comprises tribal militant outfits. The organizations in this category are a strategic choice for the second generation militants to enhance their operational capacities.

- Group Three comprises violent sectarian groups. This is also a connecting group for militants from all three generations.

- Group Four was the forte of the second generation militants and these militants have are inspired by global jihadist agendas.

2.1 Objectives and strategies

- Group One

As the conventional groups were formed to achieve certain strategic objectives of the state, the state institutions had control over their organization, training and operational affairs. However, these institutions neglected the freedom the leaderships of these groups assumed and professed, mainly in terms of empowering their religious-ideological credentials and building upon it the jihad movements in both Afghanistan and Kashmir. The state institutions were happy with the religious interpretation, so long as it supported their objectives. As these institutions’ dependence on the militants increased they deluded themselves into believing that the militants would indefinitely do their bidding. But through religious interpretation, these groups expanded their freedom and further empowered it by blending their nationalistic, or anti-India, credentials with religion.

Later, in an effort to enhance their ‘jihadist-ideological’ credentials, many of these groups established links with international Islamist and militant groups. They started considering operating independently as the nationalist cause started losing its appeal. The process picked up pace especially after 9/11.

These groups also enjoyed the freedom to give a sectarian hue to their movements, which later provided a connection between local and international sectarian terrorist groups. Most importantly, these groups created new militant narratives and strengthened them with multiple slogans. For example, the Harkatul Jihad-e-Islami (HuJI) catchphrase was ‘the second line of defense of all Muslim countries’.[20] Jaish-e-Muhammad globalized its agenda by promoting itself as ‘an international Islamic movement for waging jihad against the infidels and infidelity’.[21] Most of these conventional groups had made such slogans and objectives parts of their manifestos and the state institutions did not realize that these narratives will transform these groups and eventually make them independent.

Apart from their written agendas and slogans, these groups’ operational emphasis remained on Afghanistan and Kashmir. Their organizational expansion and operational nourishment mainly remained confined around achieving the objectives in these two territories, for they were religious-nationalist movements in character.

The secondary agenda of these groups was to bring a change in Pakistan for setting up a complete Islamic state. It was necessary for them to prioritize this agenda because they were fighting for similar causes in Afghanistan and Kashmir. The literature of these groups published during in the 1990s usually emphasized that once their goals were achieved in other territories, they would focus on Pakistan. The state institutions never took such ambitions seriously.

- Group Two

This category, mainly comprising of tribal Taliban militants, has been going through a continuous transformation. At present, the TTP and its splinter Jamaatul Ahrar are the leading components, which are shaping the ideological and political outlook of this segment. Lashkar-e-Islam and other small groups, such as Mualvi Nazir, Khan Said Sajna and Gul Bahadur groups,[22] mainly act as support groups for Afghan Taliban, the Haqqani Network and Al-Qaeda.

In order to understand the objectives of the militant outfits in this category, the inception of the TTP needs to be analyzed, since it was the TTP which provided the structure and operating framework to the outfits making up this category.

There is sufficient evidence to suggest that the Pakistani Taliban, in the beginning, were not keen on the imposition of Shariah in the tribal areas, and their primary purpose was to use the slogan of jihad to recruit fighters and collect donations to fight the ‘foreign occupation’ in Afghanistan.[23] The literature — whether in the form of publications, shabnamas (night letters), pamphlets, or CDs/DVDs — produced by the Pakistani Taliban or their affiliates in Pakistan between 2002 and 2004 indicates that the primary focus of their struggle was on waging jihad against the NATO forces in Afghanistan. Inside Pakistan, their strategy against Pakistani troops was initially defensive.[24] It was only with the passage of time that their agendas expanded, and in 2007 different local militant factions came together under the banner of TTP. The TTP adopted orthodox extremist tendencies of Takfir (declaring other Muslim sects and groups non-Muslim or out of creed of Islam), and calling for ‘Islamization’ of the Pakistani state and society.

However, it was Baitullah Mehsud who had first shaped the contours of the Pakistani Taliban movement’s objectives when he reached an agreement with the government on 22 February 2005, in South Waziristan. He had been successful in securing a guarantee from the government that he would be allowed to enforce Shariah in the area in exchange for a commitment to not send his militants to Afghanistan. Not only did he not keep his end of the deal, the pact also helped the Taliban consolidate their grip over the area. Other militant groups followed in Baitullah’s footsteps.

Baitullah formulated a four-point strategy to gain control over the area. His militants took steps against criminals; imposed and collected ‘taxes’ to speed up their operations; killed or forced out influential tribal elders who they knew could challenge their authority; and created a parallel justice system to promptly resolve disputes.[25] In Bajaur Agency alone, a single Taliban court registered 1,400 cases until August 2008 and decided 1,000 of them.[26] They established their parallel administration and appointed their trusted men to key positions.[27] Anyone who posed any ideological or tactical challenge to the Taliban rule was harshly dealt with, especially non-government organizations and formal and modern educational institutions. Taliban groups banned NGOs, targeted CD shops and attacked educational institutions, especially girls’ schools. For instance, in 2009 alone, over 48 educational institutions were targeted in FATA, which included 14 girls’ schools.[28] These local groups also contributed to the welfare of the local population in order to gain their sympathies. For instance, in June 2008, the TTP established a fund to help the victims of the military operation in South Waziristan and distributed PKR 15 million among them.[29]

The Taliban also shrewdly exploited the tribal, ethnic, and religious sentiments of this region in their favour. Flaws in FATA’s political and administrative set-up allowed the militants to weaken and gradually replace the system with their own, in the name of providing security and prompt justice to the citizenry. They also offered financial incentives to the tribesmen and recruited unemployed youth into their cadres.[30] They also employed outright coercion and intimidation to strengthen their grip on the area.

At its core, all members of the TTP alliance espoused Deobandi sectarian teachings, an attribute that allowed them to function under a single umbrella even though their political interpretation of Deobandi principles was at times not monolithic. As a combined entity, the components of the TTP maintained a dogmatic stance by espousing an interpretation that was intolerant of all other Muslim sects. This ought to have isolated the Taliban from the majority of the Pakistanis who adhere to the Barelvi tradition. In reality, this had only partially been the case since the insurgency took off, as the Pakistani Taliban craftily created a narrative around their movement that found sympathy across the sectarian divide. They strived to portray their struggle as aimed at driving out the ‘occupying’ foreign forces from Afghanistan in the short run, and all ‘infidel’ forces from Muslim lands in the long term. In framing their agenda like that, they not only tied in to transnational jihadist groups materially, but also presented themselves as ideologically similar. More tangibly, the TTP and other tribal groups including Jamaatul Ahrar and the Gul Bahadur group also tried to portray themselves as operating under the banner of Mullah Omar’s Afghan Taliban. Every militant faction that wished to join the TTP had to take an oath of commitment to the enforcement of Shariah and loyalty to Mullah Omar.[31] Through this tactic, the tribal groups hoped to gain more legitimacy and further portray their actions as justifiable, and Afghanistan-focused. This strategy was also instrumental in attracting other sectarian groups like the LeJ, and splinters of conventional militant groups to work closely with them.

An important aspect of groups in this category has been their ideological flexibility and their eagerness to gain inspiration from every new ideological tendency of the militant discourse. Groups in this category keep changing their operational and ideological frameworks.

- Group Three

The groups in this category have very narrow agendas, which makes them more focused on their operations. But these groups operate underground and need support from other organized militant groups, which influence their agendas as well and broaden their ideological horizon. The LeJ nexus with Al-Qaeda and the TTP and subsequently with the ISIS has not only broadened ideological horizon of the former but also equipped it with lethal operational tactics. It is no longer the LeJ of the 1990s, which was mostly involved in targeted killings; its new face is extensively more lethal in terms of operational capabilities and connections with terrorist groups. The TTP and other tribal groups will not let the LeJ focus only on sectarian killings but could use it to hit other targets as well, such as the security forces, foreign interests and the political leadership.[32]

- Group Four

The militant groups as well as small terrorist cells and self-radicalized individuals in this category have diverse potential and are carving out a new militant scenario in Pakistan, as they are open to absorbing new ideological tendencies and are open to establish alliances. The following characteristics distinguish them from other groups:

- They do not have formal organizational structures, which makes them dependent on big organizations.

- They are small but highly motivated groups and tend to absorb new militant ideas, as is the case with group three, but the outfits in this category have broader religious and political views.

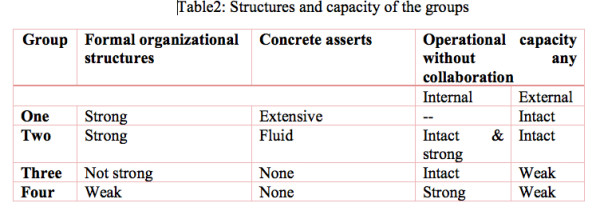

2.2 Organizational structures, assets & capacities

- Group one

Over time, the conventional groups have developed expansive infrastructure, including schools, madrassas and health centres across the country, and acquired property, offices and organizational networks, which have been difficult for their leadership to give up. The evidence suggests that such extensive infrastructure had forced them to gradually revert to their traditional nationalist agendas. Some see huge physical infrastructure and assets of conventional groups as their weakness that does not allow them to go against state.

As noted earlier, these groups actively engage in religious and nationalistic political issues. Their inclusion in Difa-e-Pakistan Council (Pakistan Defense Council) was an example of their potential to become part of the political far-right in Pakistan. This happened at a time when religious-political parties of Pakistan, considered by many as puppets of the security establishment, had started efforts to shed their image as ‘B teams’ of dictators. These parties had served the purpose of the far-right in the 1980s and ’90s. The space was there, and conventional militant groups started filling this void, while forming alliances like the Difa-e-Pakistan Council. The far-right retains the potential to trigger violent campaigns, and groups with a militant past can cause more damage in particular, especially if they feel that their interests are sufficiently threatened.

Another example demonstrates that the groups with big infrastructure also want to remain connected with the source of their ideological and religious affiliations. They try to develop their compatibility with the interest of the power centres for their own survival. When the Saudi government launched a programme in 2003 to engage religious scholars to build a response against extremist tendencies and terrorism, the impact on the Salafi clergy in Pakistan was immediately discernible. The JuD took it upon itself to condemn such thoughts among militant groups and distanced itself from all such groups and even spurned any cooperation with the Pakistani Taliban. This may help put in context the reports that the JuD was playing a role in militants’ rehabilitation in Pakistan.[33] This defines the direction of all pro-state militant groups in Pakistan and signifies the far-right’s preference for change in the country through peaceful means, while justifying the use of force to protect regional interests.[34]

- Group Two

The organizations in this category have strong but rigid organizational structures and have little potential to expand their networks beyond certain territories. They need territory to operate and beyond their areas of influence they operate through sympathizer cells. Their structural rigidness causes divisions and fissures among their ranks, which triggers new militant formations. The TTP is an example, which has been passing through continuous transformation since its inception.

The advantage for the outfits in this category is their resourcefulness; organizations in this category generate funds by tapping into both legal and illegal avenues.[35] The groups in this category are not saddled with liabilities such as offering big educational, health or other services. They mainly spend their resources to protect their territory, and launching terrorist attacks. This is one of their operational strengths.

- Groups Three & Four

A lack of organizational structure makes organizations in these two brackets operationally dangerous and these provide human resources to major groups for their terrorist plans. Their fluidity makes them a big challenge for law enforcement agencies. These groups can generate funds through criminal activity and because of their small size they can sustain their activities on minimal resources.

2.3 Nexuses and linkages

Collaborations and nexuses play an important role in determining the operational strengths of a group. This is as essential as the assets and organizational structures of the groups. The foreign militants are often ignored in threat assessments in Pakistan. But these militants play a critical role in connecting the groups and evolving operational cooperation among the militants in the country. On the threat matrix, the TTP is considered a major actor with its capacities ranging from conceiving the plan of the attack to its implementation.

There is a perception that the TTP carries out major attacks through its sleeper cells in different cities. In Pakistan, Al-Qaeda or the TTP have no need to form sleeper cells as they have extensive reach across the country through affiliates and like-minded groups of the militant streams.

Al-Qaeda’s competitive edge in terrorism expertise has influenced the Taliban and other terrorist groups in the region. Its support in the form of improved capabilities and techniques for striking their targets was a virtual lifeline for them. Typically, the influence has impacted smaller groups who had been struggling to survive or had material deficiencies and required external help to survive. Al-Qaeda has been more than willing to help them out through both ideological and operational support. The major terrorist attacks are an opportunity for smaller groups to learn sophisticated terrorist techniques.

- Prospects of disengagement & reintegration

On the basis of the findings laid out in previous sections, five probabilities for disengagement [from militant groups and violence] and reintegration of militants can be drawn:

- Probability one (P1): Disengagement from Al-Qaeda/ ISIS

- Probability two (P2): Disengagement from violent sectarian groups

- Probability three (P3): Merging with religious-political parties

- Probability four (P4): Allow some functioning under constitution and law

- Probability five (P5): Rehabilitation of the [militant] individuals

- Group One

The conventional groups’ bond with foreign groups is weakening, but they still have links with their local partners. This link can be weakened and probabilities of disengagement from violent sectarian organisations can be heightened with proper interventions. The potential for the militant groups to merge with religious political parties is minimal as most of the conventional groups are themselves on the path to becoming political stakeholders in the country. In order to neutralize violent extremist tendencies, detach the conventional militant groups from the terrorism landscape and curb hate speech, the government can consider initiating a reintegration scheme. A policy group of leading Pakistani security experts in a consultation in May 2017 held in capital Islamabad provided the framework for reintegration of conventional militant groups and suggested a Pakistan-specific rehabilitation and reintegration model, which takes into account Pakistan’s specific need, especially its democratic ethos. The group called upon the parliament to constitute a high-powered national-level truth and reconciliation commission, to review the policies that produced militancy and to mainstream those willing to renounce violence and violent ideologies. Additionally, a separate experts committee or commission, endorsed by the parliament, be constituted, which reviews the criteria for banned outfits. The group unanimously agreed that any reintegration, rehabilitation and mainstreaming of militants shall be within the frameworks of the constitution.[36]

- Group Two

The chances of success of any of the five probabilities are very low for this group, and the attraction of its resources and ideological credentials are still strong. This group needs territory to sustain its activities and for operational functionality inside the country they depend on groups falling in categories three and four. Through reducing their territorial control, their operational capabilities can be minimized. The breaking or weakening of links with outfits in groups three and four requires delicate intervention, which has less chances of success when the militant movements are at their peak.

The political activities and political mainstreaming in and around the areas of their control can reduce the level of their attraction among the local population. The development of the much needed infrastructure in FATA can act as a catalyst along with political empowerment of the local population.

The detained militants of this group can be rehabilitated, and the success of the rehabilitation process and imaginative marketing of that rehabilitation can create a big challenge for this group to retain other militant cadre.

- Group Three

Integration of outfits in this category into religious parties could be a means to curtail their violent tendencies, and moderate religious scholars can play an important role in their ideological and sectarian transformation. However, a number of constraints in this process present a huge challenge. The first constraint is the system and atmosphere at madrassas, which is still conducive for sectarianism. Compared to the non-violent religious parties, the first two groups offer more attraction to outfits in group three. The Shia and Sunni sectarian groups have limited operational capabilities, and have more chances of reintegration through religious-political mainstreaming.

- Group Four

This is the hardest group in terms of low probability of reintegration, but the chances of rehabilitation of the individuals arrested at an early stage cannot be ruled out.

There is limited scope for reintegration of breakaway factions of conventional groups. Developments such as an announcement by Punjabi Taliban leader Asmatullah Muaviya in September 2014 to stop violent activities inside Pakistan indicates such an opportunity.[37] But this announcement has not brought about any major change on the militant landscape of the country and other groups have not heeded the call. Al-Qaeda and ISIS still hold attraction for the militant groups in this category.

Outfits like Jundullah in this category are an expression of urban extremism, and most of their cadre have past links with the Jamaat-e-Islami. Religious-political parties like the JI could be persuaded to be part of the initiatives to bring the militants back to the non-violent discourse and decrease the attraction of global militant movements.

The outfits in this category comprise the third generation of militants in Pakistan, who attract the first generation and inspire the second. The state and society have to join hands to break up their connection and association to deal a decisive blow to militant extremism and violence in Pakistan.

4. Conclusion

The study of behaviours of the militant groups in Pakistan suggests little prospects of reintegration and mainstreaming of the militants into the society. The reintegration prospects can be explored within the conventional militant groups. The formation of the MML by the JuD, is an attempt by a militant group to legitimize its actions and avert international sanctions, although some argue that participation in the democratic process may provide an opportunity for JuD leaders to further review their narrow social views and ideology.

End Notes

[1] Author’s interview with Haji Javed, a member of Jamatud Dawa, Lahore, August 11, 2017.

[2] M. Amir Rana, “Choking financing for militants in Pakistan,” in Moeed Yusuf, ed., Pakistan’s Counterterrorism Challenge (Washington: Foundation Books, 2014).

[3] Daily Mashriq (Urdu), Peshawar, February 7, 2005.

[4] M. Amir Rana, et. al., Dynamics of Taliban Insurgency in FATA (Islamabad: PIPS, 2010), pp. 86-95.

[5] Ibid, p. 75.

[6] Ibid, pp. 89-95.

[7] Ibid, p. 79.

[8] Ibid.

[9] M. Amir Rana, “Structural violence,” Dawn, January 14, 2012. http://www.dawn.com/news/688190/structural-violence.

[10] Usman Kurd was killed early 2015 in an operation conducted by security forces in Balochistan’s provincial capital Quetta. (Source: Amir Meer, “Killing of Usman Kurd a major blow to LeJ,” The News, February 17, 2015, https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/24495-killing-of-usman-kurd-a-major-blow-to-lej)

[11] One of the founding members of the LeJ, Malik Ishaq was killed, along with his two sons and 11 others, in an alleged encounter between police and militants in Muzaffargarh, south Punjab, in July 2015.

[12] M. Amir Rana, “Punjabi Taliban,” Dawn, July 9, 2010, http://www.dawn.com/news/546022/the-punjabi-taliban.

[13] M. Amir Rana, “New formations,” Dawn, September 7, 2014, http://www.dawn.com/news/1130346/new-formations.

[14] Author’s non-structured interviews with police officers in Islamabad, including Farhan Zahid, Raza Shah and Asim Gulzar.

[15] Author’s non-structured interviews with prominent religious scholars Maulana Ragib Naeemi, Mufti Muhammad Zahid and Dr Rasheed Ahmed in Islamabad

[16] Data is derived from Pak Institute for Peace Studies’ digital database on conflict and security: http://san-pips.com/app/database.

[17] M. Amir Rana, “Why Pakistani Taliban matters?” Dawn, June 30, 2012, http://www.dawn.com/news/730812/why-pakistani-taliban-matter.

[18] Author’s interviews with police officers in Islamabad.

[19] For details, please see M. Amir Rana, The Militant: Development of a Jihadi Character in Pakistan (Islamabad: Narratives, 2015).

[20] M. Amir Rana, A to Z of Jihadi Organizations in Pakistan (Lahore: Mashal Books, 2009), p, 270.

[21] Ibid, pp. 216-17.

[22] Maulvi Nazir was killed in a drone strike in South Waziristan in 2013 but his group is still active. Similarly Khan Said Sajna was reportedly killed in a drone strike in 2015 inside Afghanistan, and reports about the death of Gul Bahadur in a Pakistani military strikes also emerged in 2014. The groups established by the latter two are also operational. The Sajna group is also known as Mehsud Taliban and claimed some recent attacks in South Waziristan including an IED attack against head of a peace committee Wali Jan Mehsud on November 30th (2017) that killed 5 people including Wali Jan in Spinkai area of the agency. (Source: Dawn, December 1, 2017, https://www.dawn.com/news/1373980)

[23] Mullah Nazir, interview by Jamsheed Baghwan, Daily Express (Urdu) Peshawar, May 13, 2007.

[24] For details see Pak Institute for Peace Studies, Understanding the Militants’ Media in Pakistan: Outreach and Impact (Islamabad: PIPS, March 2010).

[25] In August 2008, Baitullah reorganized the Taliban “judicial system” and brought all the courts under a ‘supreme court’ and appointed Rais Mehsud as its chief justice. (Source: Dawn, Islamabad, August 17, 2008).

[26] Yusaf Ali and Javed Afridi, “People throng Shariat Court to get disputes resolved,” The News, Peshawar, August 4, 2008.

[27] Khalid Aziz, The News, Islamabad, June 1, 2008.

[28] The data and information are derived from PIPS digital database on conflict and security which documents incidents after monitoring media reports.

[29] Daily Ummat, Karachi, June 7, 2008.

[30] M. Amir Rana, et. al., Dynamics of Taliban Insurgency in FATA, p. 153.

[31] This information is drawn from interviews with resources persons in FATA who requested anonymity.

[32] M. Amir Rana, “Epitome of hate,” Dawn, January 12, 2013, http://www.dawn.com/news/778418/epitome-of-hate.

[33] Michael Georgy, Pakistani with U.S. bounty said helping de-radicalize militants, Reuters, April, 7, 2012 – https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pakistan-usa-bounty/exclusive-pakistani-with-u-s-bounty-said-helping-de-radicalize-militants-idUSBRE8350BA20120407

[34] M. Amir Rana, “The bounty and crown,” Dawn, April 11, 2012, http://www.dawn.com/news/709800/the-bounty-and-crown.

[35] M. Amir Rana, “Choking financing for militants in Pakistan,” in Moeed Yusuf, ed., Pakistan’s Counterterrorism Challenge.

[36] Pak Institute for Peace Studies, “National strategy for inclusive Pakistan: a policy framework for secure and cohesive Pakistan, June 2017, http://pakpips.com/downloads/inclusive-pakistan.pdf.

[37] Tahir Khan, Watershed event: Punjabi Taliban renounce violence, The Express Tribune, March 6, 2016, https://tribune.com.pk/story/762038/watershed-event-punjabi-taliban-renounce-violence/

(Muhammad Amir Rana is the director of Pak Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS). He was a founder member of PIPS when it was launched in January 2006 and had previously worked as a journalist with various Urdu and English daily newspapers from 1996 until 2004. He has worked extensively on issues related to counter-terrorism, counter-extremism, and internal and regional security and politics. The views expressed are the author’s personal academic views. This occasional paper is published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Mapping terror and Insurgent Networks” project. All Mantraya publications are peer reviewed.)

To download a PDF version of this occasional paper click here. Pakistan-based militant groups & prospects of their reintegration

Mantraya Occasional Papers are peer reviewed research papers of approximately 5000 words. The themes of occasional papers conform to Mantraya’s identified project themes. Researchers are encouraged to submit unsolicited papers to office@mantraya.org. To read earlier Occasional Papers, click HERE.